Figure 14: The data from 1860s Gooding’s Township indicates that 100% of area slaveholders were white. This outcome was not surprising, as by 1860, Craven County had only one non-white slaveholder, a mixed-race woman named Catherine Stanly (Watson 310). She and her family have been studied extensively as some of Craven’s most prominent free African American slaveholding residents. While further research into the Stanleys and Craven’s other black slaveholders is necessary to a full understanding of the local slave system, this work should not eclipse or in any way soften the study of white slaveholders, who dominated the institution at large.

Figure 15: In 1860, 18 of Gooding’s 23 slaveholders (or a total of 78.3%) were male. Three individuals (or 13%) were female. The remaining 2 (8.7%) represent joint holdings in which individuals of diverse sex received equal shares. In both cases (GT60-1013CCSH and GT60-1019CCSH), these holdings were composed of minor children who had been willed slaves by a deceased parent. Likewise, the female slaveholders (GT60-1001CCSH, GT60-1008CCSH, and GT60-1012CCSH) appear to have been unmarried women who received slaves upon the death of a spouse or relative.

These results are in keeping with what is known about antebellum gender norms, especially those relating to the holding of property. During this era, the property of married women was controlled by their husbands. This means that any slaves a married woman received would be held in his name. Unmarried women’s property would have been held in their own names. Both men and unmarried women could hold property for minors, with the property being held in his or her name, as well as the names of the minors he or she represented. The representative would have had control over and use of the property until the minors came of age, and/or the property had to be divided.

Figure 16: In 1860, 15 (65.2%) of Gooding’s 23 slaveholders listed their primary occupation as farming. 3 (13%)-all minors-had no occupation. 2 (8.7 %) said that they were housekeepers, while the final three (4.3% each) described themselves as a Baptist minister, shingle maker and seamstress, respectively. The seamstress and the housekeepers were all unmarried women, while men made up the other workers. As rural community, it makes sense that the majority of Gooding’s residents were involved in agriculture. This field was traditionally dominated by white men who owned and/or managed most of the farm land. As the data from Gooding’s reflects, unmarried white women mainly engaged in household management or gender-specific task work, such as washing or sewing.

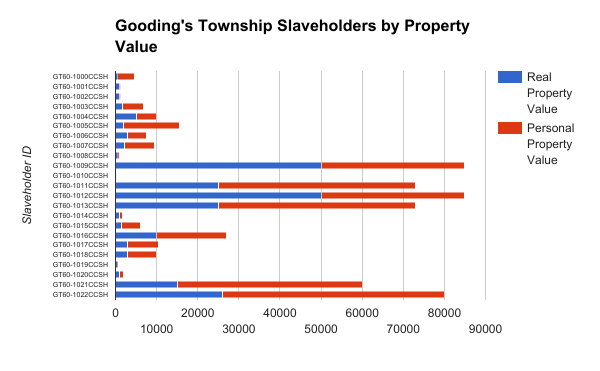

Figure 17: The majority (14/23) of Gooding’s Township slaveholders fell towards the lower end of the economic spectrum, with a net property value of less than $10,000 (about $294,000 today) (Williamson). For most of these individuals, the bulk of their wealth was held in personal property, such as slaves. The same was true of Gooding’s richest individuals, a fact which may explain why the area experienced economic turmoil post-Emancipation.

One surprising feature of the data is that many of the poorer slaveholders were non-farmers. The poorest of all the slaveholders was shingle maker William L. Ballinger (GT60-1010CCSH). This somewhat challenges the narrative which presents the average Craven County slaveholder as a poor farmer. While most of Craven’s slaveholders were indeed poor, over half were not engaged in agriculture. Poor individuals did make up the majority of farmers, however. Very few of Gooding’s slaveholding residents fell between the $10,000 and $60,000 marks, supporting the idea that Craven had very little social stratification.